Getting ready to do some Dangerous Cutting once again.

Sources

from: Adam Smyth’s review of A Humument

Yet, unique as A Humument may appear to be, it belongs to a lengthy literary-artistic tradition. The 18th-century culture of extra-illustration, or ‘grangerising’, was sparked by James Granger’s Biographical History of England (1769): readers remade books by pasting in prints of eminent figures. Four years before Phillips bought A Human Document in 1966, Joe Orton and Kenneth Halliwell anticipated Phillips’s bawdy relationship with literary inheritance by stealing books from Islington libraries and remaking them by creating new collage covers, subtitles and dustjacket blurbs. They were sentenced to six months in prison. Among other improvisations, Orton and Halliwell pasted a monkey’s head onto Collins Guide to Roses; adorned a volume of John Betjeman’s poems with a photograph of a heavily tattooed, elderly man in swimming trunks; and glued pictures of giant cats onto the cover of Agatha Christie’sThe Secret of Chimneys. At about the same time, a related tradition of artists’ books reached some kind of a peak with Dieter Roth, who not only reworked found comics and newspapers, but also mixed pulped books with onions and spices to create Literature Sausage.

When Phillips stumbled across Mallock’s novel, he had just read an interview William Burroughs gave to the Paris Review in 1965, and had been experimenting with cutting up copies of the Spectator. Phillips later visited Burroughs: ‘I had a very tough day with him,’ he recalled in 2011. ‘Very fierce. Incredible. Fearsome … Generous. He took a day out of his life to spend with me. Not that we had lunch or things like that. An entirely bare room with nothing to sit on. Agony, the whole thing.’

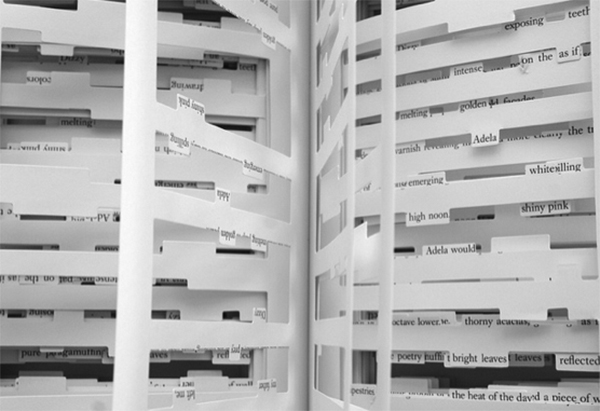

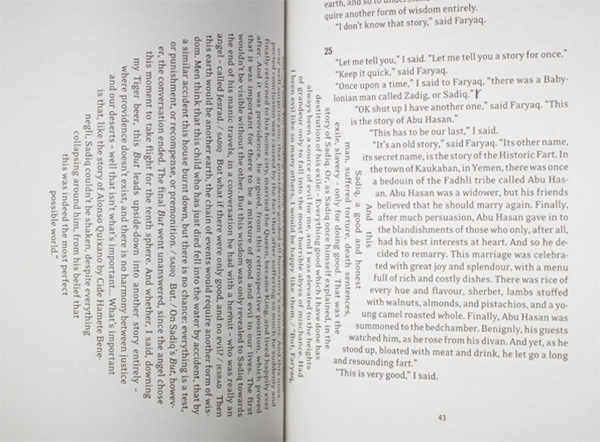

Recent experiments with the novel’s material form are indebted to Phillips. Jonathan Safran Foer produced Tree of Codes (2010) by cutting away most of the text of his favourite book, Bruno Schulz’s short story collection The Street of Crocodiles (1934; translated into English in 1963), to leave behind a new story (slicing seven letters from ‘Street of Crocodiles’ leaves ‘Tree of Codes’); its fragile pages are largely composed of gaps. The volume is, among other things, a homage to Schulz, a Jewish writer murdered by the Nazis in 1942. Adam Thirlwell’s Kapow! features an array of typographical tricks – blank space, folded pages, blocks of text set at right angles – in an attempt to track the non-linear thinking of a narrator during the Arab Spring.